Italian Neo-realism signified the post WW2 reaction of Italian filmmakers against the censorship of Mussolini’s regime, and as a statement against the predominant ‘telefoni bianchi’ (white telephone) films of the 1930s and 40s. “Italian Neo-realism has been seen as a moment of decisive transition in the tumultuous aftermath of world war which produced a stylistically and philosophically distinctive cinema” (Shiel, 2006, pg. 1). The cultural and cinematic shift that Italian neo-realism introduced was seen as “a symbol of the people’s will to be free” (Brunetta, 2003, pg. 109), and captured on screen the immense devastation and depression that followed Italy’s fascist past. As the name suggests, Neo-realism was all about capturing realism; social realism to be precise, with general characteristics of “realistic treatment, popular setting, social content, historical actuality, and politic commitment” (Bondanella, 2001, pg. 31). This blog will focus on the origins of Italian Neo-realism through texts such as Rome, Open City (Rossellini, 1945) and highly regarded Neo-realist texts such as Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948), analysing the significance these texts have within the Neo-realist movement, and discuss the influence such texts have had on cinema and culture throughout the years up until the present.

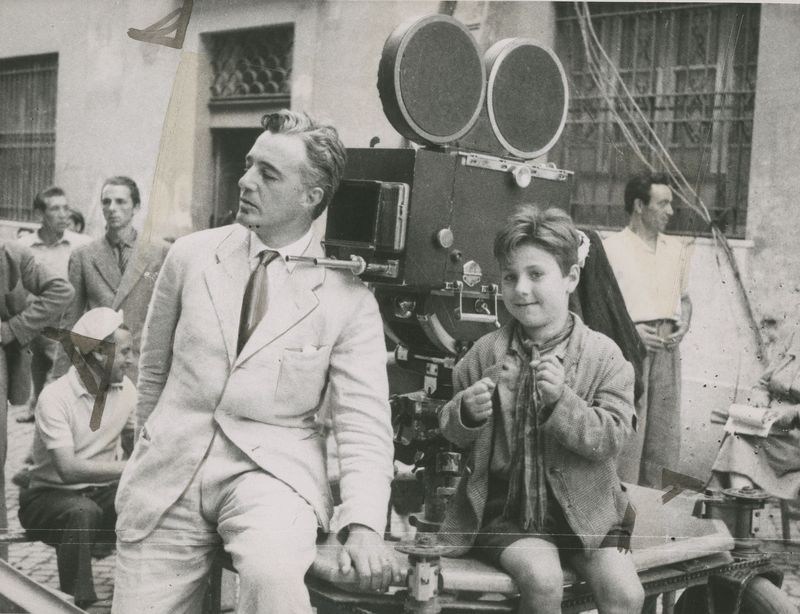

“By 1944-1945, Italian film could no longer be ‘suppressed’” (Liehm, 1984, pg.60). Rome, Open City is considered one of the first Italian Neo-realist films, given that shooting began whilst Italy was still under German control. Liehm, a key academic within studies of Italian Cinema and Neo-realism, commented on the influential impact the text had within Italy and its people; “Open City is a film about death and an awareness of the tragic in ordinary life […] The novelty of Open City lies in its transformation of art into information. Rossellini provides the viewer with a real memory of something the viewer has not actually experienced” (Liehm, 1984, pg. 63-65). Rome, Open City essentially opened the floodgates for Italian filmmakers to make films such as Bicycle Thieves, and further the conversation regarding the effects of post-war life and the depression of everyday people, and speak freely without censorship.

Bicycle Thieves tells the story of Ricci, an everyday man who requires a bicycle to be able to work; however when his bike is stolen, he must hunt down his prized possession to maintain his employment and provide for his family. De Sica uses the bicycle as a plot device to tell a much dark and neo-realistic tale; “Such deceptive simplicity, or self-concealing art, makes the film, like Antonio’s bicycle, the bearer of far heavier and more sophisticated cargo than its fragile exterior would immediately suggest” (Marcus, 1986, pg. 56). De Sica’s text can be seen as an attempt to convey a grounded and humanizing message to the audience that reflected the time: “the film may also be seen as a pessimistic and fatalistic view of the human condition, as well as a philosophical parable on absurdity, solitude, and loneliness” (Bondanella, 2001, pg. 59). The following clip shows the ‘fatalistic’ view that De Sica shows within Bicycle Thieves, when a lifeless boy is pulled from the river.

The qualities of Italian Neo-realism filmmaking have provided influence throughout various movements within cinema, particularly the French and the British New Wave respectively. The French New Wave, a movement that sprung into creation in the late 1950s, was heavily inspired particularly by the Neo-realist style of location shooting; “One decisive New Wave action was to move away from studio-bound cinema. The New Wave thereby inscribed itself into a Rossellini-inspired gesture, following in the tradition of Rome Open City (1945)” (Marie, 1997, pg. 81). The British New Wave was also heavily inspired and influenced by the filming techniques and practices used by Italian filmmakers during the Neo-realism period. Amanda Lay comments extensively on the strong influences that British New Wave filmmakers took away from Neo-realism; “it is perhaps Italian Neo-realism which most influenced the British New Wave directors […] these (British New Wave) films are variously described as working class realism […] or simply as social realist texts” (Lay, 2002, pg. 60).

Whilst the movement of Italian Neo-realism may not have inspired a political response from fellow European countries, it is clear to see the technical and filmmaking aspects that were found within Rossellini, De Sica and other Neo-realist directors were seen as an important. These new approaches to filmmaking were crucial when it came to the birth of other movements in cinema; “The influence of Italian neo-realism can be seen in a host of different national new waves that rippled out across Europe in the late 1950s and 1960s” (Lay, 2002, pg. 60).

Word Count: 468

Peer Review:

After a detailed look at my fellow student’s blogs, I have decided that in cohesion with the marking criteria (subject content, presentation, tone, research and formalities), UP903550’s blog is the best overall. The subject content shown throughout demonstrates great knowledge of the topic and set films, and the presentation complements this with interesting, relevant videos and captivating images. The blog shows a clear development in experience, with both use of tone and the extent of research increasing with each blog post. The formalities of the blog, such as spelling and grammar, are near flawless throughout, and provide a clear and engaging reading for those that may wish to read the blog. The use of strong primary and secondary sources used provide a more thorough argument, allowing for clearer conclusions to be made. The use of tools such as hyperlinks have been used effectively, to provide readers with an extension of knowledge and research around a particular subject, and support the blog’s integrity as a well-researched piece. Overall, this is a fantastic example of how to present and execute an undergraduate student blog, and is a shining example of a student who has carefully examined their feedback and the marking criteria to create an excellent blog.

Bibliography:

Bondanella, P. (2001). Italian Cinema: from Neorealism to the present. New York: The Continuum.

Brunetta, G.P. (2003). The History of Italian Cinema: A guide to Italian film from its origins to the Twenty-first century. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

De Sica, V. (1948). Bicycle Thieves [Motion Picture]. Italy: Ente Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche.

Lay, S. (2002). British Social Realism: from documentary to Brit Grit. London: Wallflower Press.

Liehm, M. (1984). Passion and Defiance: Film in Italy from 1942 to the Present. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Marcus, M. (1986). Italian film in the light of Neorealism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Marie, M. (1997). The French New Wave: An artistic school. Paris: Editions NATHAN.

Rossellini, R. (1945). Rome, Open City [Motion Picture]. Italy: Minerva Film SPA.

Shiel, M. (2006). Italian Neo-realism: Rebuilding the city. London: Wallflower Press.